Essay

HAMLET’S CAMERAS: NOTES ON MYSTICAL MEDIUMS AND MEMORY

by Emmalea Russo

“Must I remember?” — Hamlet

“Loss binds with the very act of recalling and recollecting; alteration is conservation’s other face.” — Régis Debray

0

Near the beginning of Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1603) and Michael Almereyda’s film Hamlet (2000), Claudius says:

Though yet of Hamlet our dear brother’s death

The memory be green, and that it us befitted

To bear our hearts in grief and our whole kingdom

To be contracted in one brow of woe,

Yet so far hath discretion fought with nature

That we with wisest sorrow think on him

Together with remembrance of ourselves.

Here, green = fresh, raw, unhealed, new, scab unformed.

A wound inflames, proliferates, and remodels.

A leaf transmutes green, yellow, red, brown.

In his book on photography, Roland Barthes says it’s the punctum, an imperfection or mark in the image’s field which pierces or wounds that remains with the viewer as injurious trace. We enter this inexplicably intoxicating error again and again, each time new, with forgetting and alteration in-between, as memory.

Dismemberment, decay, scatter, burn, and rot comprise and enable human memory.

Dis/re- member.

To die, to sleep – / to sleep, perchance to dream.

What happens when, digitally stored and played-back evermore, memories and wounds don’t have the time and space requisite for morphing, mutating, de- and re- composing? When the distance between event and recollection – a textured arena which houses/makes mutations, revulsions, and anxieties shrinks as it quickens into a smooth loop?

1

Saint Augustine devotes the tenth book of his Confessions (398 AD) to a lengthy reflection on memory, performing the process of recollecting and connecting images in the mind’s storehouse:

The affections of my mind are also contained in the same memory. They are not there in the same way in which the mind holds them when it experiences them, but in another very different way such as that in which the memory’s power holds memory itself. So I can be far from glad in remembering myself to have been glad, and far from sad when I recall my past sadness.

Incongruity is part of the pleasure and surprise of remembering. Past affections layer the now, creating ineffable space between what you were and what you are: I can be far from glad in remembering myself to have been glad…

Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

The Burnout Society (Isabella Gresser, 2015)

“With my tongue silent and my throat making no sound, I can sing what I wish,” writes Augustine. Hold and release are simultaneous. The muscles and mind hold an image, lozenge-like, while Augustine is free to be quiet. He can be two places at once performing two divergent maneuvers, multiple and magic. In remembering, what grips is also what grants weird wings. In Michael Almereyda’s Hamlet (2000), Hamlet’s 21st century predicament matches his 17th century one. He sees the ghost of his dead father who tells him he died by poison and wants Hamlet to take revenge, can’t let go and seems to be going mad, makes a film in order to catch the conscience of the king, kills Ophelia’s father by mistake, and fights in a duel where everyone dies by poisoned sword.

Ophelia (Julia Stiles) burning a photograph in Hamlet 2000.

In 2000, Hamlet’s mediums for transmission and recording are different. In the remixed Hamlet, words are images, the play is a video, and the ghosts and humans communicate and proliferate through screens and various handheld machines. In The Disappearance of Rituals, Byung-Chul Han argues that digitization and the disappearance of memory-creating rituals make a topology of the present where “Time lacks a solid structure. It is not a house but an erratic stream. It disintegrates into a mere sequence of point-like presences; it rushes off.” Nietzsche’s claim in On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), that a thing must be burnt in order to stay in the memory, that destruction is necessary for hold, anticipates Barthes’s wounding punctum and recalls the burnt offering, where something is destroyed as it’s brought nearer to the divine, and thus made sacred.

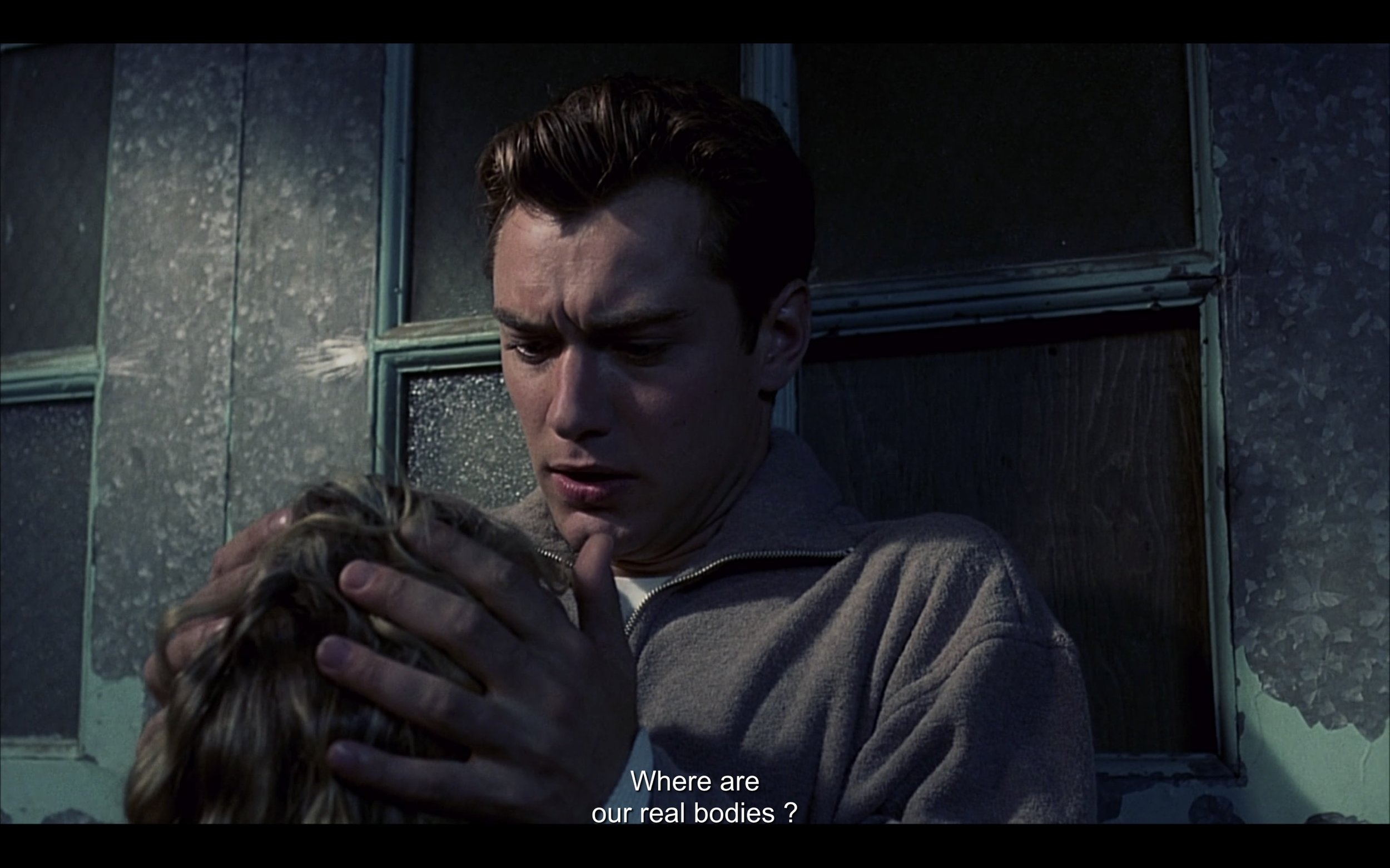

Inside an internet-like videogame in eXistenZ (David Cronenberg, 1999)

2

Hamlet 2000 opens in Times Square, where the most concentrated concatenation of images in New York City, injected with neon, squares time and space into pixels. In the days preceding January 1, 2000, we worried about how the machines which mediate our lives would handle the jump from 1999 to 2000. Hamlet 2000 occupies this transitional moment, straddling analog/digital, videos/streaming, there/not-there, 20th/21st century, as Shakespeare’s Hamlet straddles the passage from an apparently medieval to an apparently modern world.

“I’ve lost all my mirth,” says Hamlet into the camera.

“I’ve lost all my mirth,” says the video recording of Hamlet one second later.

Hamlet loses his mirth to and on the screen. His mirth-loss loops. He can’t lose the loss.

LOSSofMIRTHLOSSofMIRTHLOSSofMIRTH

LOSS OF MIRTH ( ) MEMORY OF LOSS

I’ve lost all my mirth.

I’ve lost all my mirth.

I’ve lo

st all m

y mirth

my all lost I’ve

mirth

mirth

mirth

We carry memories and they move (through) us without warning as paradoxical operations.

Agatha and the Limitless Readings (Marguerite Duras, 1981)

3

Act 3 opens in a New York City Blockbuster video store where Hamlet, dressed in his mourning clothes, roams.

To be or not to be…

To act or not to act?

Is the screen dreaming us?

Hamlet at Blockbuster (Michael Almereyda, 2000)

Video footage from the myriad televisions in the store seep into his famous soliloquy. Place, like time, is out of joint, as the Blockbuster is what anthropologist Marc Auge calls a non-place, a liminal zone symptomatic of globalized late capitalism and defined by homogeneity and consumerism. In Non-Places: An Introduction to the Anthropology of Supermodernity, Auge writes: “The space of non-place creates neither singular identity nor relations; only solitude, and similitude.” Airports, supermarkets, freeways, screens, places for passing through. In non-places, text tells us what to do.

ACTION

ACTION

ACTION

Action is an aisle. The non-placed self gets mirrored perpetually back. The Blockbuster, by now a kind of relic, is both familiar and nondescript, or as poet Anna Moschovakis writes in You And Three Others Are Approaching a Lake: “The New Violence: I visited a country where everything looked like home.” The first Blockbuster opened in 1985 in Texas. By 1992: 2,800 stores and more on the way. In 1997, Netflix and other streaming services appeared. In 2010, Blockbuster declared bankruptcy.

4

Cables powering the internet in All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace (Adam Curtis, 2011)

14th century, angels turning the heavenly spheres.

Polonius (Bill Murray) speaking into a surveillance camera in Hamlet 2000.

A videographer, Hamlet carries around a tiny video camera, a proto-smartphone on which he watches footage of events right after they happen.

Like angels (heavenly messengers and surveillance mechanisms), Hamlet’s media is environmental and networked, everywhere testifying to some larger power.

We first meet Hamlet’s dead father as a televised ghost while Hamlet reviews old video footage. Then later, as spirit.

Ophelia’s flowers are photographs of flowers.

In On Photography (1977) Susan Sontag writes:

Cameras define reality in the two ways essential to the workings of an advanced industrial society: as a spectacle (for masses) and as an object of surveillance (for rulers). The production of images also furnishes a ruling ideology. Social change is replaced by a change in images. The freedom to consume a plurality of images and goods is equated with freedom itself. The narrowing of free political choice to free economic consumption requires the unlimited production and consumption of images.

Sontag assigns surveillance to rulers and spectacle to the masses but in Hamlet 2000, each character is both spectacle and surveillance mechanism: SPECTACLESURVEILLENCE.

Ophelia is forced to wear wires to record an intimate conversation with Hamlet.

Polonius speaks directly into a surveillance camera.

Finally, everyone haunts everyone. Or: everyone is a recording device being recorded. Who can be trusted? What escapes recording? What/who leaves a mark?

5

Between 1292-1296, the Italian mystic Angela of Foligno recounted her divine experiences to her confessor, Brother Arnold. Angela’s recollections describe long periods of waiting interspersed with occasional ecstatic unmediated contact with the divine. She recalls what God told her: “There are times in which I come and go, but throughout a great number of cities, there is no soul in which I rest as I rest in yours.” About this transmission, she says: “He then told me the number of cities, but I do not remember it.” When her confessor interjects, wondering if these cities might be measurable in length or breadth, Angela says no: “It was ineffable.” She frequently notes that her words cannot do justice to her experience, that nothing can explain or capture these flashes of direct contact, thrilling and traumatic.

Panel depicting of one of Angela of Foligno’s visions (Gaetano Gandolfi, 1791)

Among the technological mediums for altering memory that appeared during the middle ages: spectacles, watermarking, paper, rotating bookmarks, and glass mirrors. For many medieval mystics, devotion was a process of being on hold, a kind of graceful and muscular passivity marked by alternations of God’s painful absence and dazzling presence. Recollection and anticipation become fuel for transmission as Angela’s writings perform formally the divine (dis)appearances she recounts, often making grand statements then promptly canceling them out. Neither the angels nor the saints can comprehend what she’s experiencing:

…the divine and ineffable workings which were realized in my soul were such that no saint or angel could tell of them or explain them. I am convinced that there is no saint, angel, or creature which has anywhere near the capacity to understand these divine workings and that extremely deep abyss. And everything I am saying now is so badly and weakly said that it is a blasphemy against these things.

Angela’s angel-defying ecstasies are filled with gaps and anxiety. In Revolt, She Said, Julia Kristeva writes:

It is precisely a technocratic ideology that is supposed to abolish anxiety. But what I am saying is the opposite: anxiety, repulsion, nothingness are essential aspects of freedom. That’s what revolt is. When one abolishes revolt that is linked to anxiety and rejection, there is no reason to change. You store things and keep storing. It’s a banker’s idea, not an idea of a rebel, which spreads this technocratic ideology.

In The Ecstasy of Communication, Jean Baudrillard describes a kind of ecstasy engendered by constant communication:

Obscenity begins when there is no more spectacle, no more stage, no more theatre, no more illusion, when everything becomes immediately transparent, visible, exposed in the raw and inexorable light of information and communication. We no longer partake of the drama of alienation, but are in the ecstasy of communication.

To be in a state of ecstasy is to be driven out of oneself, to (however briefly, thrillingly, fearfully) stand outside of the I. One is here. One is also there, on screen, as an image and gleaming under the raw inexorable light of information and communication. This light, as Byung-Chul Han points out in Transparency Society, is not exactly light, but rather see-through lightless radiation, penetrating and intrusive. Metaphysical light sourced from the sun or divinity creates hierarchy and processual order whereas transparent non-light carries power differently, as in Hamlet 2000 where surveillance cameras, glass houses, and reflective smooth surfaces proliferate. The new violence obliterates light and shadow with see-through mediums, hypermediation gets ecstatic where everyone everywhere is present all the time everyone everywhere present here and now even when they are absent everyone everywhere present….

In the Phaedrus (c. 370 BCE), a dialogue on metaphysics, love, and rhetoric, Plato records Socrates’s concerns about the technology of writing: “It will implant forgetfulness in their souls. They will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks.” New technologies have always altered memory and concerned philosophers. Coupled with ideologies of technological transcendence and the whitewashing of negativity, where we store things and keep storing, technological mediums for recall become strange analgesics set to forever-loop. Hamlet is a philosopher, writer, lover, image-maker, image, recorder, recording-device, and mystic given to ecstatic instants. Grief disjoints time and digital recall disjoints grief. What see-through ecstasy is this?

11th/12th cen. wall painting (detail)

Emmalea Russo lives at the Jersey shore and edits Asphalte Magazine. She's the author of two books of poetry/essay, G (2018) and Wave Archive (2019), as well as several artist books and chapbooks. Currently, she's working on a series of projects on film and medieval mysticism. Her website is https://emmalearusso.com/