MEANDERINGS: Genesis of the Acknowledge exhibition at Umbrella Studio, March 2018

by Anneke Silver

A childhood in the Netherlands… I was born in the city of The Hague; my childhood home was in a well-to-do area on the edge of the city. We overlooked a landscape, flat from horizon to horizon, crisscrossed by rectangular networks of channels and dikes. (No wonder 17thC Dutch painters became famous for painting skies. And Mondrian in the 20thC for painting rectangles!)

Half of the Netherlands is below sea level; it is preserved with ingenious, cleverly engineered pumping systems- (dating from the time of functioning windmills)- which keep the ground water levels steady, and the North Sea out!

There was World War 2, casting a gloom over this landscape: barricades of barbed wire, ominous military, sorties to find produce. During the worst winter, with no power, fuel or food. There was darkness and cold; Air raid sirens and the sound of bombs exploding; ruined houses just around the corner.

Is it surprising than that as a child - despite a loving family- I dreamt of being elsewhere: in an exotic environment, enjoying tribal life, finding sustenance in tropical forests and swimming in sparkling streams cascading from distant mountains. I became highly critical of the man-made, unnatural world; and to me unreal—without soul.

Picture then the young adult arriving in North Queensland. My imagined landscapes came to life, crystal-clear streams, rainforests, and mountains.

After years of travelling, exploring the tropical north, sailing its islands- savouring the magnificence of the environment , we built our place on the river in Townsville’s Upper Ross area. It meant daily immersion in this completely natural piece of bushland that was itself, and had been there forever. My connection deepened, and I felt compelled to explore different modes of expression. I could no longer paint the landscape in the traditional Western way, with its one-point perspective-- a spectator outside the landscape looking in. For me it is in no longer ‘over there’. It becomes me. It is part of me, and I am part of it. I start to feel connections, a murmur of the tree , rhythms created by the conversation between breezes, the sound of birds and insects. There is something intangible, which I don’t feel anywhere else in the world’s other wild landscapes. There is a definite vibe, And the more I learned of indigenous culture, the more indigenous people I met and worked with, the more I realised that this landscape still vibrates with song lines, stories and knowledge. I start to feel that I am connected to something, something perhaps that indigenous people call being ‘on country’.

I wanted to show what I felt. I wanted to show it as something sacred.

I have always loved the format and the old gold of traditional religious icons of the Greek and Russian Orthodox churches with their multiple images, telling stories around a central image. Perhaps because the narrow street I walked through to my weekly art class in the inner-city, was full of little antique shops. Many with a rich variety of icons on display. In one of these, a restorer sat in the tiny shop window. I was fascinated and watched progress from week to week.

Recalling these experiences, I decided to create small wooden objects, adorned with real gold leaf which allude to the icon, replacing images of the traditional scenes and saints, with what I felt were the saints and ‘stories’ of the Bush. I chose not to paint a traditional landscape but instead I wanted each element to be a symbol that stood for something and invited interpretation rather than passive absorption. The forms emerged by reducing foliage shapes, tree trunks, animal and bird shapes, mountains, flowers and rocks—to their minimal essences. I called them Bush Icons

Interestingly, the reductions of shape necessary for the bush icons influenced larger paintings that I made on canvas that I made of the riverbank. I reduced elements there as well, over-painting more obvious representation, leaving essential marks. It often looked like some sort of script. Titles were among others- Scribblings of the Tree Spirit. Changes of light and colour during the day fitted seamlessly into the three-fold structure borrowed from the earlier icons . I made paintings such as A Day between Nights in which I had divided the canvas in three vertical panels. Stylising shapes, and thinking of them as Landscape Saints, invited many wonderful explorations. It kept me close and intimately connected to the riverbank landscape.

Often working as a tutor for what was then called the Flying Art School, flying small aircraft at low altitudes, I became aware of a different view of the land. The most exciting were the big rivers and tiny creeks wriggling unencumbered like snakes through the landscape. They have a will of their own , flow for hundreds of kilometres totally un-interfered with. I contrast this to the waterways of my childhood country where there is not one single waterway that has not somehow been straightened, made into a channel with sides of neat wooden palings, or bricks, encumbered with locks and bridges. For me there is an intense pleasure in following a river’s course, both from the air or in real time. The exhibition titled Rivers: un-cut exhibition became all about celebrating this freedom: the wanton power, the fertilising influences on the land; picking their way, taking seemingly random turns, almost doubling back on themselves; fine veins feeding them from wooded ranges. Opening wide into the sea at a spot it chose for itself. I can’t even begin to explain how much I enjoy this display of total freedom. And the beauty of its patterns not just the shapes, twists and coils of the rivers but the shapes around them; the riparian borders, grasslands, dotted patterns of trees --all influenced by the river, all in complete harmony—perfection!

Looking at the land in this way made me see the similarities between these patterns and many of the artworks by indigenous artists. It also prompts questions in relation to Australian history…the atrocious events of colonisation. Indigenous people were hunted and killed. The landscape seen from the air makes our history so clearly visible; the disregard for the original people and environment —land-use knowledge accumulated over eons ...snubbed. Rainforest drastically cleared; verdant creeks turned in to drains.

So, one of the final works in the Rivers:un-cut show was a large triptych (a mode of working inherited from my icons). The first one of the triptychs is the image of a pristine natural world, rhythms and shapes; textures as seen from above in a map-like format. The middle one is all in blue. The landscape is still pristine in form, but it comments on the voyages of the early 17th C explorers, which were the Dutch.* The blue colour refers to Delft blue ceramic tiles, depicting their sailing ships. The pristine land was ‘discovered’. The third panel depicts the present-day attitude to the environment. The landscape is divided into a grid of squares, stretched across the canvas with black woollen thread; growing sheep being the first activity to do irreparable damage to the fertile plains that had been nurtured by indigenous nations. The grids take no notice of natural forms, the natural run of water; thoughtlessly visualised into rectangles, ready to be sold or exploited. No reference to an existing population and their patterns. Between those three canvases I placed two narrower ones -literally squeezed- between the larger wider works, which show indigenous northern language groups. I was deeply touched when an indigenous viewer had a long look at the work. I asked him if his language group was represented. He nodded thoughtfully, and pointed, saying ‘it is there’. We both realised that it was acknowledgement.

I felt that this message had to be the subject of a whole exhibition. Almost without a break I explored this for my next show titled Acknowledge.

I was now more aware of the destructive policies in relation to indigenous culture. It seemed symptomatic of the whole colonising thrust to not only kill and displace First Nation people, but also wipe out all memory of the original landscape and the culture that shaped and conserved it.

Reading Bruce Breslin’s Exterminate with Pride), and Timothy Bottoms’ Conspiracy of Silence on I learned how bad our history really is; how dense and widespread the killings and poisonings were, right here in our own area. Just about every creek, every station, and every waterfall has seen people ambushed and killed- evidence removed because it was officially against the law.

The horrors recorded in Bottoms’ book shook my perception of history to its very foundation, causing distress down to a physical level. I deliberated on how to deal with the ‘acknowledge’ part of this exhibition. My mind gyrated like a compass gone wild. Did I want this exhibition to be about all the atrocities? Am I that sort of artist? Is it my role? Perhaps yes, perhaps not. Indigenous artists, such as Judy Watson have made this their life’s work. She recently created a massacre map of Australia, which made news in the New Yorker; Fiona Foley managed to place one in front of the Magistrate’s Court in Brisbane.

Perhaps my role for this exhibition was to limit comment to my own encounters.

I can never have the depth of connectedness to country as an indigenous person. But somehow, I want to acknowledge that I know it exists, and that I understand a little. I wanted to acknowledge that the way I interpret the landscape is because of that special feeling.

But I also wanted to acknowledge that I know what went on in these places. What visual language could I turn to?

There is no way that I would use the image making of the indigenous culture itself. That would be stealing yet another thing. Western colonisation has stolen enough. I experimented in a couple of works, using dots in a western way, which basically created Impressionist images. Not a very strong message at all.

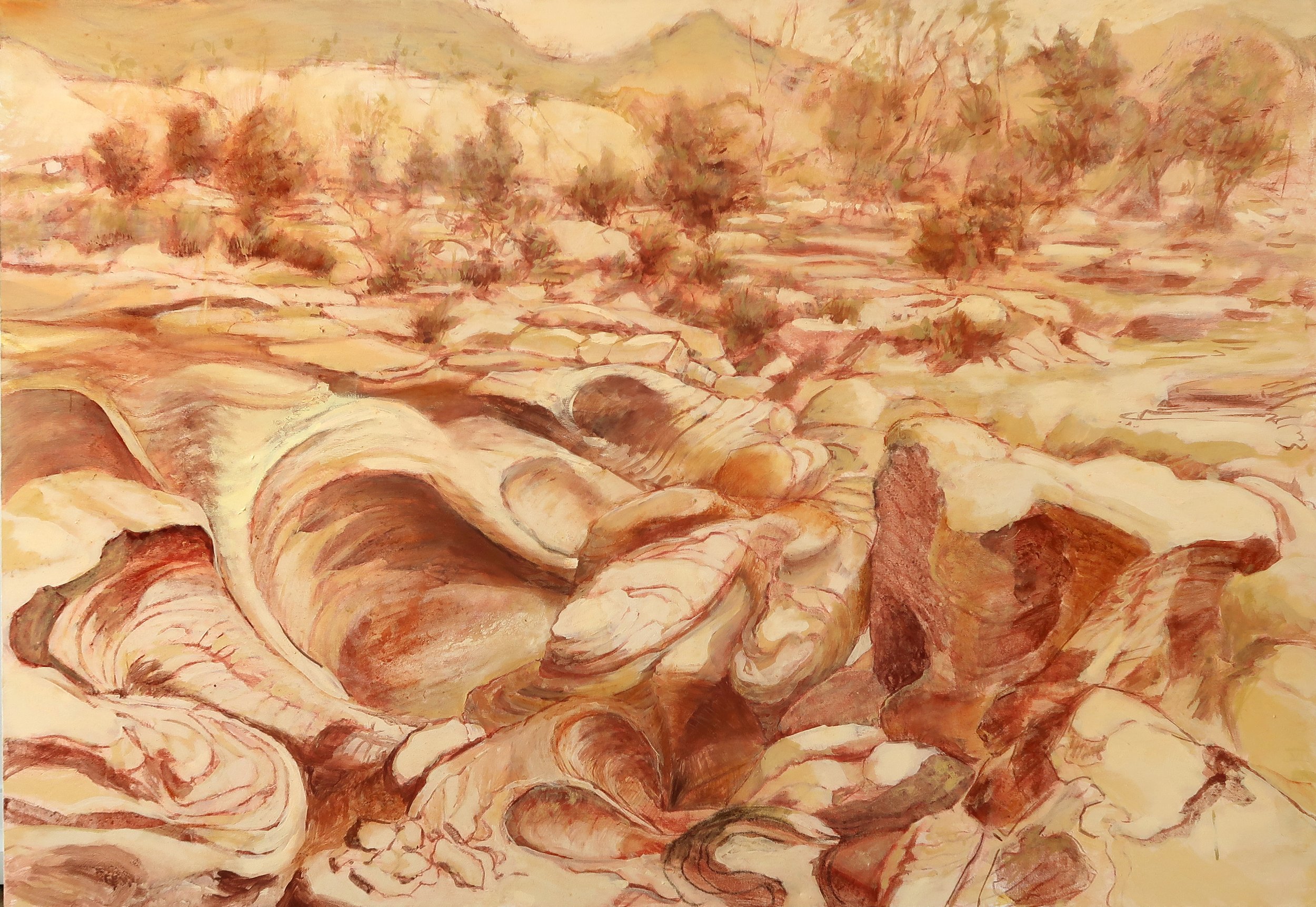

I spent time camping near the dry sandstone bed of the Flinders River, North of Hughenden. While drawing the myriads of complex intertwining shapes of the sandstone it came to me that these patterns, in a range of ochres, were a metaphor for a culture and a people had that been around since time began. Pattern based on landscape is part of indigenous art practice; I extracted my own pattern in a way different to theirs to highlight the flow, in acknowledgment of that other tradition. I called it Convergence/Divergence.

Still not a very clearly understood statement.

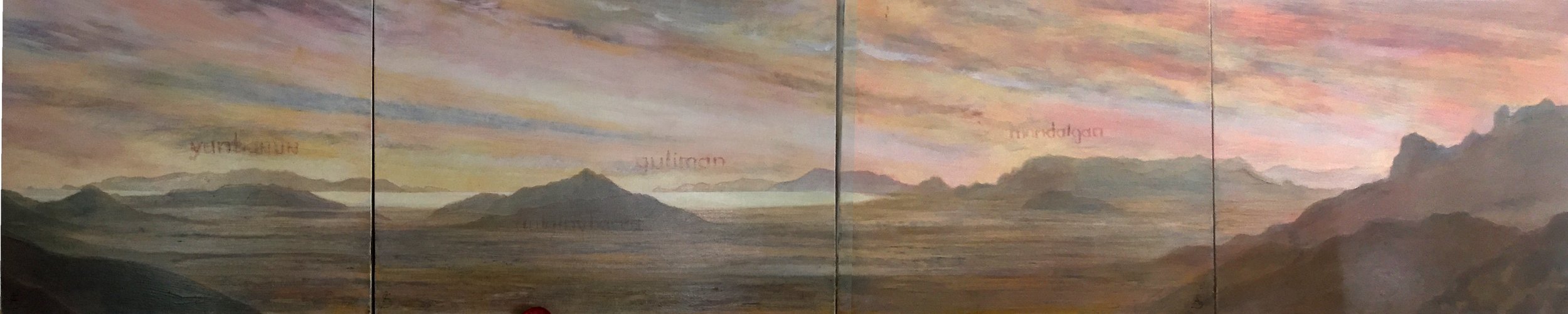

There is a view I love. It is of Townsville, seen from the top of Hervey’s Range. Until very recently the city was practically invisible. I inserted the local indigenous names of landmarks into the painting in collaboration with Russel Butler, an Elder. Appropriately named Hidden City. Most Australian landmarks were re-named. For thousands of years, they had names that resonated with the environment. Replacing the original names and condemning even the seasons as ‘not proper’*, seems to express a wish for the land to be something else – nostalgia for England, Ireland or Scotland; an unconscious drive to be something we are not. We have a much longer history; better to be proud of it, and acknowledge it. Naming landmarks after those who ‘discovered’ them must stand as a lasting insult

especially when it is now clear that many of those ‘discoverers’ were complicit in the crimes committed.

The use of text in the painting prompted me to take a stronger approach.

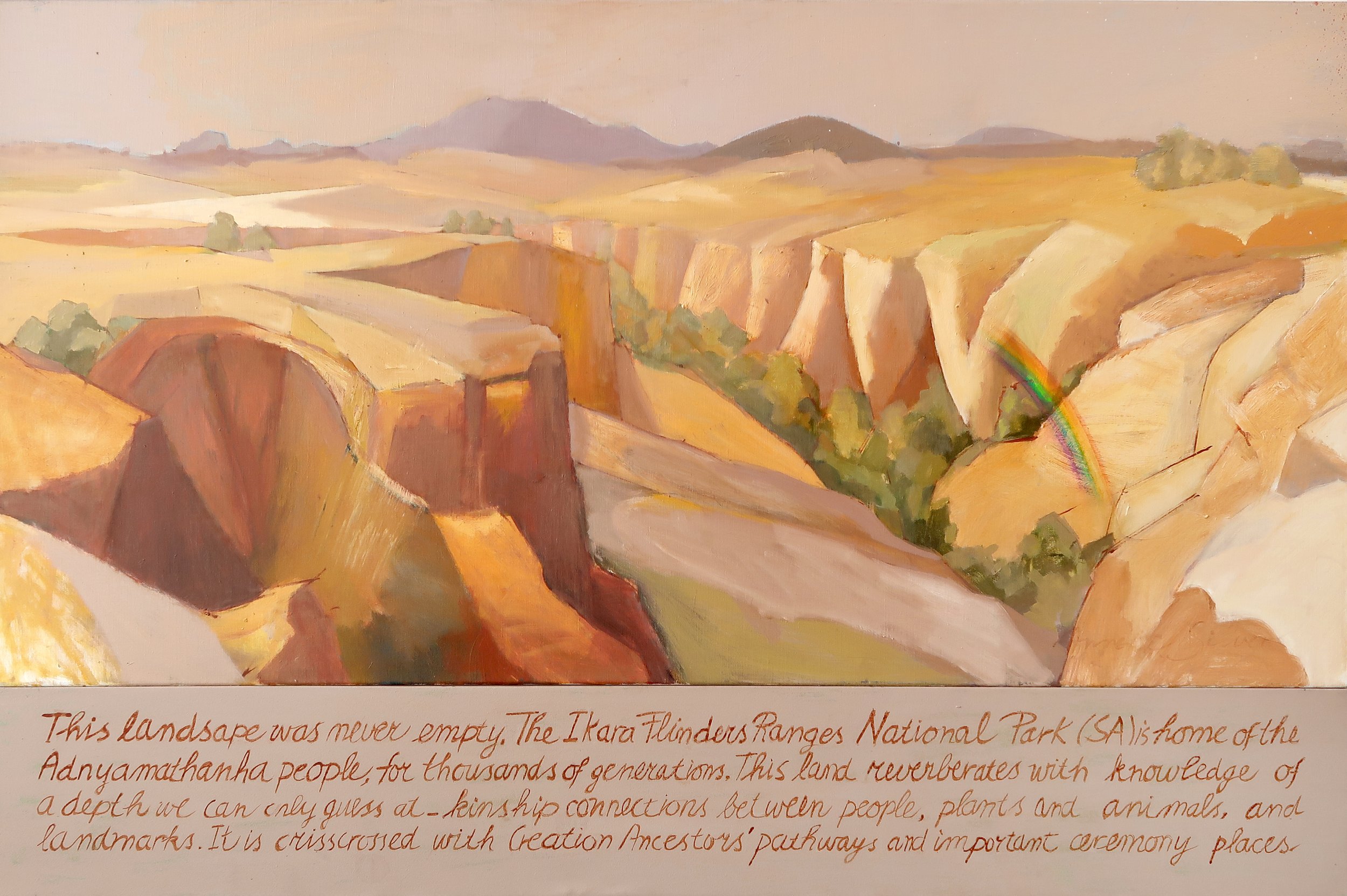

I decided to paint a location of significance, showing its beauty and resonance. . A location. Then what? It had to be text. I could only express the atrocities with a text. These were placed as a conjoined panel below the painting, the meaning of the text colliding with the beauty of the landscape.

The apparent emptiness of the landscape can be misleading as it was in the days of the killings. The land was never empty. In Secret Waterfall, only the rainbow above the gorge reveals that water and people are present. The text states the original owners’ name.

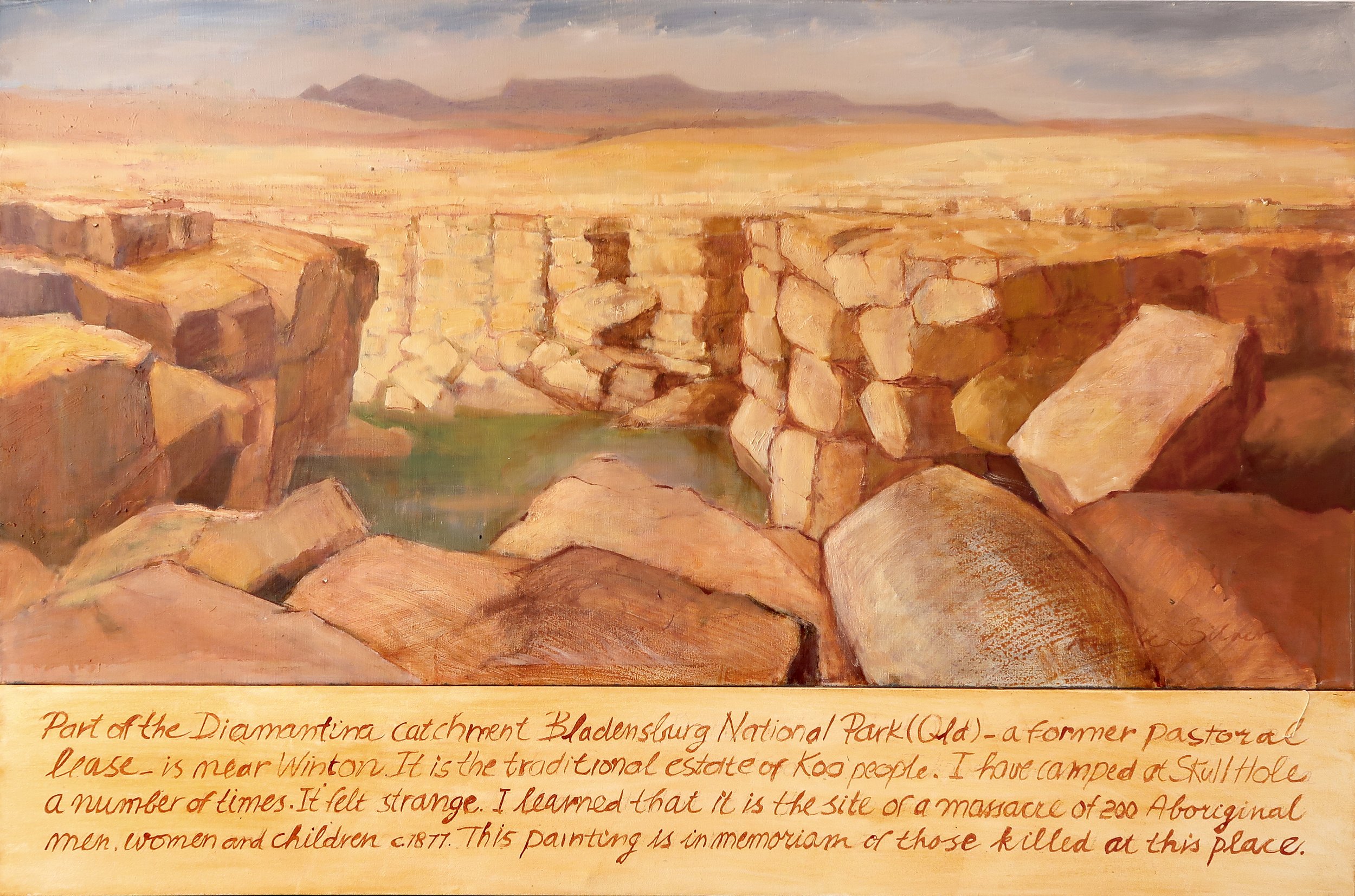

There are many places in the world where memories persist when people have gone... places like Gallipoli, the killing fields of Cambodia, or Auschwitz. Skull Hole in Bladensburg National Park was something like that for me, full of strange vibes. Timothy Bottoms’ findings from private diaries and newspaper cuttings made it clear, beyond doubt, that there had been a “ dispersal” -a massacre- in this location. . The term ‘dispersed’ is a euphemism to avoid criminal charges. When ‘no arrests were made’ was added in official reports, it meant ‘all were killed’. Many skulls were found there and collected by Lumholtz. The facts are spelled out in the adjacent text panel. I called this work Memorial, to honour the memory of those who were killed in the battle to defend their country.

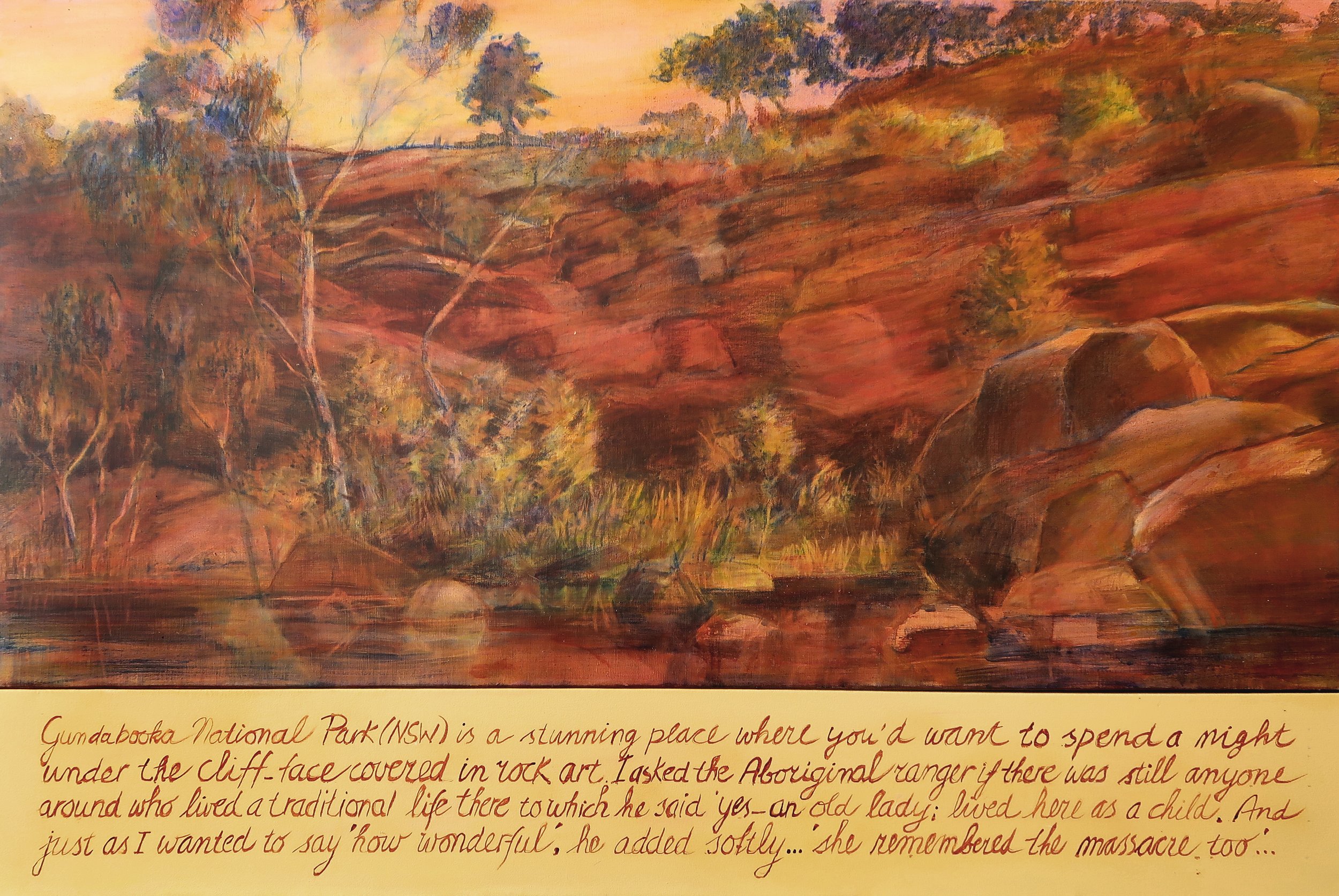

In contrast to Skull Hole, another site- at Gundabooka National Park- near Bourke, felt wonderful; a truly magical place, with lots of rock art in the large overhanging cliff face. An idyllic spot with a small creek running just below it. The rock paintings had rows and rows of stick figures—a bit like you see on the back window of some cars: husband, wife, five children and cat, dog or fish. In my mind’s eye I could see the people represented by the figures, almost heard them talking and laughing and children playing in the creek. I asked the indigenous Ranger if anybody was still alive who lived there as a child perhaps. His reply affected me deeply :” ‘yes there was an old lady in town, who remembered’, he said. I was about to reply, ‘marvellous’ or something like that, when he added softly ”she remembered the massacre too”. Even writing this it gives me cold chills.

With this exhibition, I wanted to acknowledge that I am aware of the way indigenous people imbued the land we live on with meaning; something we can only guess at and feel by being mindful, by acknowledging a shared love for ‘Country’.

I also acknowledged the atrocities committed, and that we can no longer be ignorant of those. And that I perhaps understand that a little too from having an early childhood in an enemy occupied country, with raids, fear of random executions and places called ‘home’ destroyed.

We cannot change the past, but we can commemorate. For instance, we cannot change the historical facts of Gallipoli either. But we can, and do commemorate.

Why should we not commemorate what happened with Indigenous people. As a nation we might find healing from such an action, find resolution by acknowledging the truth.

It would also be wise to be respectful, by taking note of First Nation traditional knowledge and attitudes, which were so different from our culture of environmental exploitation. The indigenous way of owning is to be responsible for— to care for. Respect in traditional Indigenous culture was not based on how much stuff you owned, but how much knowledge you had, and how well you carried out the responsibilities flowing from that knowledge. Modern society can well learn from this before we completely destroy the planet with our rampant consumerism. It might help us to appreciate this northern landscape for what it is and to be mindful of its special qualities.

* I sought to demonstrate that we do have seasons, ‘proper’ to north Queensland. It was the subject of my PhD Seasons without Names.

**They named many of the coastal places: Arnhem land; Cape Keerweer and Cape Leeuwin; Staaten and Nassau rivers ; Van Diemen’s Land renamed Tasmania after Abel Tasman. They named Australia, New Holland.

***The ‘dispersal’ was headed by Acting Sub-inspector Robert Wilfred Moran (1846–1911) and his troopers and a group of settlers headed by George Fraser - 14 men in all. The target was a large camp with hundreds of people at Skull Hole.

Sources:

Bottoms, T.; Conspiracy of Silence

Breslin, B.; Exterminate with Pride

Mahood, K.; Position Doubtful